Modular and lightweight elimination of transaction reordering attacks

Orestis Alpos, Ignacio Amores-Sesar, Christian Cachin, and Michelle Yeo

We tackle the problem of sandwich attacks in decentralized finance (DeFi) in a general way. We introduce a protocol to transform any blockchain consensus algorithm into a new one that has the same security, but in which sandwich attacks are no longer profitable. Our protocol is fully decentralized with no trusted third parties or heavy cryptography primitives. It makes existing blockchains resilient to such attacks in exchange for increased latency until consensus becomes final and by adding a small computational overhead.

Sandwich attacks

Sandwich attacks account for a loss of \(1.3\) M USD over the last 30 days for users of Ethereum Eigenphi.

In most blockchain networks, validators have access to incoming transactions at the moment they enter the network and before consensus on them is reached. Transactions are usually disseminated with a gossip protocol among the peers. Some validators play a special role in consensus and may select the transactions for a particular block and determine their order within the block. In a sandwich attack, such validators exploit this power to gain an unfair advantage.

Consider an innocent transaction that swaps one asset \(X\) for another asset \(Y\) in a decentralized exchange. Many trustless DeFi exchanges compute the relevant rates automatically based on a fixed algorithm and the current reserves they hold; a typical example are constant-function market makers such as Uniswap.

Suppose a profit-seeking validator observes such an \(X\)-to-\(Y\) swap transaction \(\textit{tx}^\ast\) issued by an unsuspecting client. To maximize its own advantage, the validator can exploit this knowledge and insert its own \(X\)-to-\(Y\) exchange transaction \(\textit{tx}_1\) before \(\textit{tx}^\ast\). This is an example of front-running due to insider knowledge, such insider trading may also occur in traditional finance, where elaborate regulations and preventing methods aimed to prevent that. The validator will use the computed exchange rate and sell, say, \(k\) units of \(X\) to get units of \(Y\). All other things being equal, the client’s transaction \(\textit{tx}^\ast\) will subsequently execute at a slightly worse exchange rate than if \(\textit{tx}_1\) was not there. To finish off the attack, the validator back-runs the client’s swap with another transaction \(\textit{tx}_2\) of its own that exchanges units of \(Y\) back to \(X\). The validator again manipulates the transactions landing in the block to its own advantage. Typically, it will obtain more than \(k\) units of \(X\) at the end. This shows how consensus validators may profit from their privileged position and their insider knowledge. These and related attacks have had significant economic impact on DeFi markets (Eigenphi).

Randomizing the order

An important technique to mitigate this problem is thus to remove the control over the positioning of the transactions in the block from the validators. Assume a random order is imposed within a block \(B\) and let us focus on three transactions in \(B\), the client’s transaction \(\textit{tx}^\ast\), the front-running transaction \(\textit{tx}_1\), and the back-running transaction \(\textit{tx}_2\). Since any relative ordering of these three transactions is equally likely, \(\textit{tx}_1\) will be ordered before \(\textit{tx}_2\) with the same probability as \(\textit{tx}_2\) before \(\textit{tx}_1\), hence, the validator will win or lose with the same probability.

We achieve a random order without a third party by introducing the Partitioned and Permuted Protocol, abbreviated \(\Pi^3\), a novel efficient decentralized algorithm that does not rely on external resources and that counters sandwich attacks effectively. Protocol \(\Pi^3\) determines the final order of transactions in a block \(B\) created by a validator \(V_i\) through a randomly chosen permutation, denoted by \(\Sigma\).

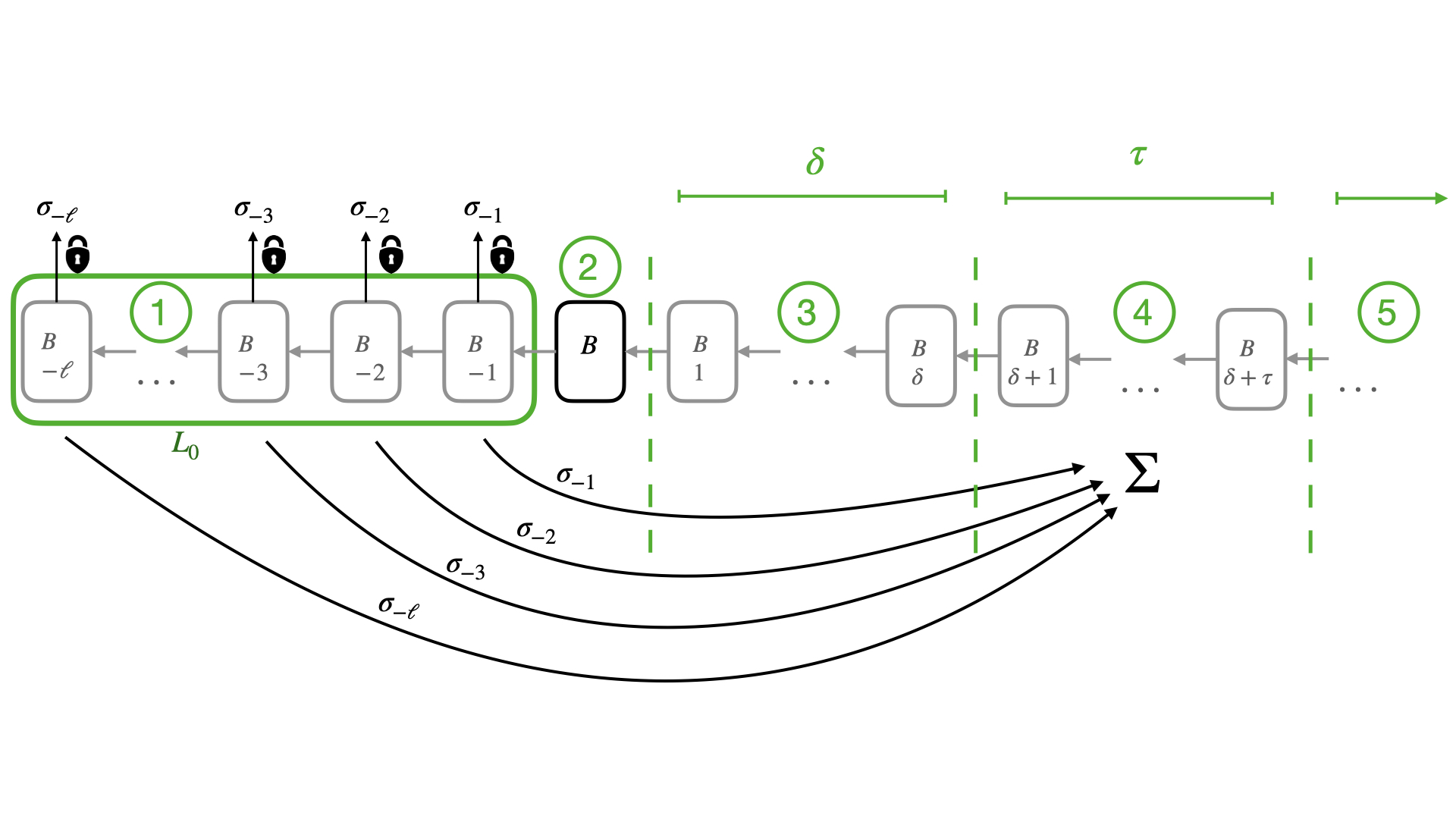

Obviously, one cannot trust a single validator or a third party to pick this randomness in a fair way. Instead, \(\Pi^3\) lets a set of leaders select a fresh, random permutation \(\Sigma\) for each block. These leaders are the validators that created the most recent blocks in the chain. But note that the permutation \(\Sigma\) for the current block \(B\) must not be known until after \(B\) has been created, otherwise the validator \(V\) creating \(B\) would have the option to use \(\Sigma^{-1}\), the inverse of \(\Sigma\), to initially order the transactions in \(B\), so that the final order is the one that benefits \(V\). Protocol \(\Pi^3\) overcomes this by making \(\Sigma\) known only after \(B\) has been fixed some \(\delta\) blocks later. But this introduces another problem because \(\Sigma\) could be influenced after creating \(B\) by a coalition of such leaders that bias it to result in a more profitable outcome for themselves. For these reasons, \(\Pi^3\) has the leaders (1) commit to their contributions to \(\Sigma\) before (2) \(B\) becomes known and thereby produce unbiased randomness. To incentivize leaders to open their commitments during a period of \(\tau\) blocks (4), \(\Pi^3\) employs a delayed reward release mechanism that only releases the block reward to leaders when they have generated and opened all commitments (5) after an additional delay of \(\delta\) blocks. The waiting period (3) is inserted before the opening of the commitments to prevent that the validators rewrite block \(B\). As shown in the figure below.

Increasing the randomness

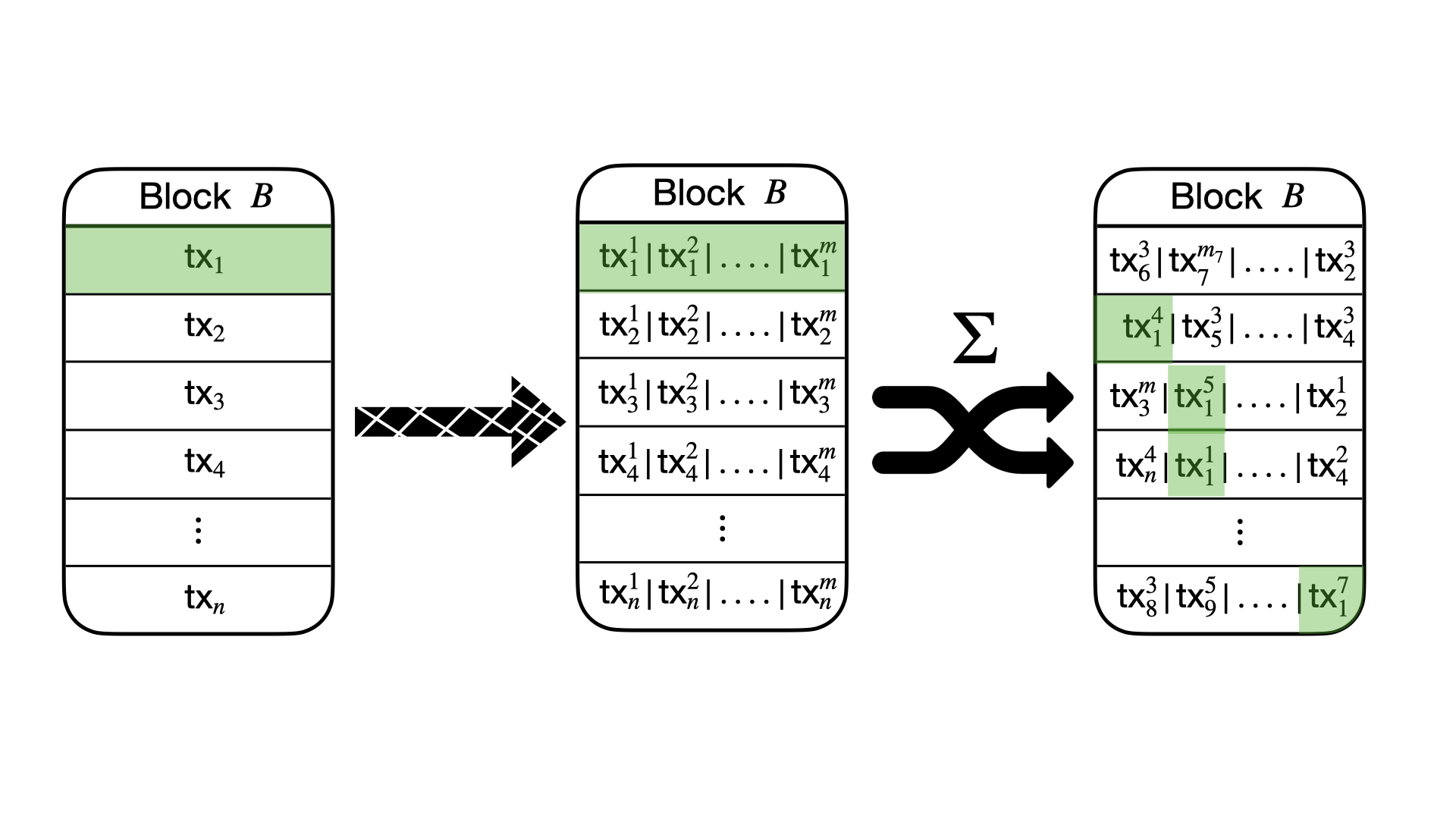

In some cases, however, performing a sandwich attack might still be more profitable than gaining the block reward, and hence a leader might nevertheless choose to not reveal their commitment and thereby bias the resulting permutation. In general, a coalition of \(k\) leaders can choose among \(2^k\) permutations out of the \(\ell !\) possible ones, where a block is formed by \(\ell\) transactions. It turns out that the probability that \(\textit{tx}_1\), \(\textit{tx}^\ast\), and \(\textit{tx}_2\) appear in that order in one of the \(2^k\) permutations is \(\frac{1}{6}\). Protocol \(\Pi^3\) mitigates this by dividing each transaction into \(m\) chunks, which lowers the probability of a profitable permutation in two ways. First, the number of possible permutations is much larger, \((\ell m)!\) instead of \(\ell !\). Second, a permutation is now profitable if the majority of chunks of \(\textit{tx}_1\) appear before the chunks of \(\textit{tx}^\ast\), and vice versa for the chunks of \(\textit{tx}_2\). The probability of a profitable permutation approaches zero rapidly as the number of chunks \(m\) increases. Protocol \(\Pi^3\) is summarize in the diagram below.

For a full version we refer to our research paper that has recently been presented at the OPODIS 2023 conference.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: